Rula Halawani and the Power of Bearing Witness

Behind the lens, Rula Halawani finds a subversive power in telling stories of Palestinian life

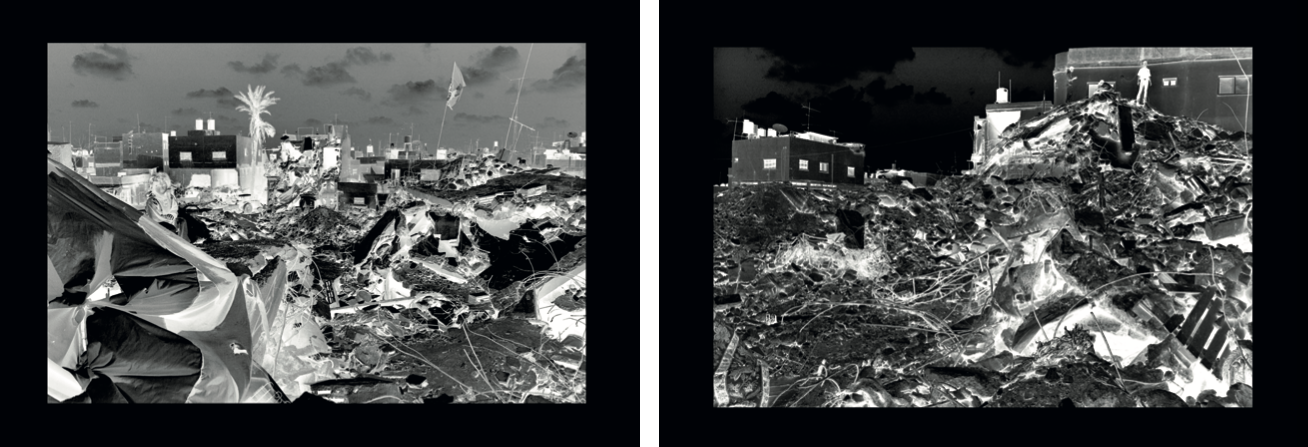

Rula Halawani, Untitled XIII, from the series Negative Incursion (2002) sepia print / Rula Halawani, Untitled XI, from the series Negative Incursion (2002) sepia print.

With text by Reem Farah a freelance writer with a keen interest in art, politics, and their intersections.

Rula Halawani was majoring in Mathematics and Physics at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada when she accidentally, yet auspiciously, discovered photography. Engrossed in a slide deck projected onto a classroom wall in the summer of her penultimate year, Halawani instantly knew that taking photographs was what she wanted to do. And so, as the first Intifada ensued in her homeland, Halawani switched majors and received a Bachelor’s degree in Photography.

Being from Palestine and far from home instills a sense of responsibility in Palestinians. Although she practiced photography as an artist, she wanted to witness what she had missed while living outside the country during the first Intifada. When Halawani returned to Palestine, she did so as a photojournalist.

Halawani conceives of this early period of her career not in technique or in achievements, but in the sequence of deaths she witnessed, each one etched in her memory beyond photographic detail, a fact that demonstrates the peculiarity of how the Arabic words for witness and martyr share the same root: شهد. The funeral of the martyr Nidal Al Allousi in Nablus, for example, was the first that Halawani witnessed as a photojournalist, and the first time she saw a corpse, that of a child. Shebegan to ask, “Why are people dying? Why are they willing to die for their land?” This question drove her investigation as a photojournalist. While she does not answer this question, she reflects her own intimacy with the land. In Irrational (2003), she photographs a landscape multiple times, as if blinking between each take. Halawani notes, “There are no longer growing ancient villages melting into the mountains, there are no shepherds wandering freely, no olive trees hugging the beautiful hills.” In Traces (2007), she documents the environment that surrounds the separation wall as it is being built as a fact on the ground, capturing the landscape that it divides.

On the eve of the Aqsa Massacre in 1990, Halawani left her home in Jerusalem, camera in hand, to photograph the site. As she snapped photographs, a man intentionally pushed her, smashing her camera to the ground. As Halawani picked up the pieces and mourned the burned film, she found a sense of subversive power in being witness to a regime that attempts to erase her. The power of occupying space on her own land inspired a profound realization in Halawani. Instead of asking, “Why do people die for the land?” she began asserting, “People need the land to live.” This is evident in the series For My Father (2015), which commemorates the landscapes that surrounded her upbringing, where her Palestinian father raised her. Being from Jerusalem, she continues to reflect on the shifting boundaries beneath her feet. Over the course of Halawani’s lifetime, Jerusalem has become fragmented into an archipelago whereby Israel confiscates more land. According to a 2010 Human Rights Report, only thirteen per cent of East Jerusalem was zoned and accessible for Palestinian construction. The non-profit organization Grassroots Jerusalem found that, in 2014 alone, Israel demolished 590 Palestinian homes in the city, and continues to make Palestinian lives unlivable in an effort to forcibly displace them.

Rula Halawani, all images, Untitled, from the series For My Mother (2020) archival pigment print.

In 1997, Halawani was assigned by Reuters to photograph clashes in Hebron. She had come across this neighborhood and its residents many times before. A boy she knew who loved to play football was murdered before her eyes for stone throwing. Witnessing the murder of yet another young Palestinian boy left her feeling lost. She felt that to witness death was no longer enough to report effectively on Palestine. Instead, she wanted to use her work to tell stories about Palestinian life and resigned from her job as a photojournalist. In sharing this story today, she notably remembers the boy not as a stone-thrower, but as a footballer.

After deciding to commit herself to her artistic practice full-time, Halawani dedicated the next few years to honing her craft and was accepted to art residencies in Marseilles, Chicago, and London. Her dream was to teach photography to a new generation of Palestinians; so she completed her graduate degree in London, again with a full scholarship, then founded and directed the photography program at Birzeit University. In 2002, after the second Intifada broke out, and as the incursion of the West Bank took place, Halawani dropped everything to go to the site of conflict with only her camera. At Jenin refugee camp, she heard the stories that her father used to tell repeat themselves. She produced the series Negative Incursion (2002) in x-ray format, revealing the impact of violence that is otherwise invisible.

Departing from her early documentary photography, Halawani now manipulates what she sees through the lens of her camera with experimental techniques; because the instrument itself cannot reveal colonization or evidence occupation. A wall is not just a wall. In The Bride is Beautiful but She is Married to Another Man (2017), she uses an x-ray machine to scan photos multiple times, altering them with each copy of a copy, as she imagines the physical and psychological impact on Palestinians, who are

forced to continuously pass through surveillance security technology. In her recent work, she depends on archival photographs as they express a history of intimacy between Palestinians and their land.

Halawani refers to her projects as “art stories.” They are housed in international collections including the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, and the Victoria & Albert Museum, London; and were recently exhibited at the Venice Biennale. Charlotte Cotton, the curator of the 2021 Sheikh Saoud Al Thani Project Award, which the artist received, describes Halawani as “an exceptional artist who has continually navigated and examined the consequences of occupation upon the cultural narratives and contested land of her native Palestine.” She has, in so many ways, shown us that to be both photographer and Palestinian is to witness critically, to feel viscerally, and to tell urgently. It is up to us to listen as well as to see.