The Sky Oscillates between Eternity and Its Immediate Consequences: An Interview with Nadim Choufi

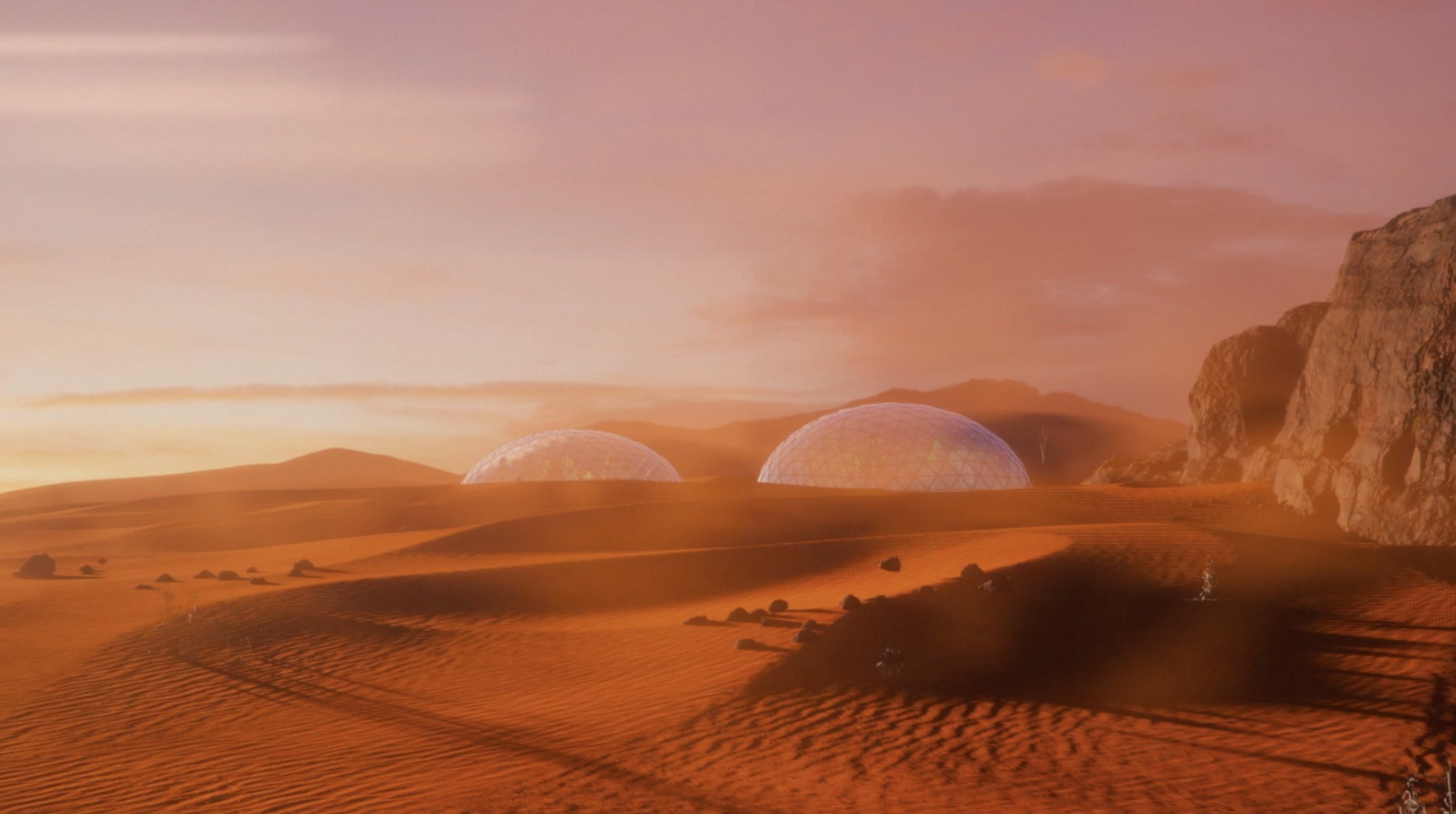

Nadim Coufi, The Sky Oscillates between Eternity and Its Immediate Consequences still, 2021. Courtesy of the Artist.

With text by Hind Mezaina.

Nadim Choufi’s The Sky Oscillates between Eternity and Its Immediate Consequences is an eighteen-minute film set in a space colony on Earth composed entirely of digitally rendered environments and stock footage. Based on news about the construction of Mars Science City in Dubai, the film addresses how the future of smart cities relies on the promise of “sustainable” closed systems in the face of health and ecological crises. Two protagonists narrate how the control and exploitation of environmental life cycles and organisms become a blueprint to achieve such futuristic visions.

The film is Nadim Choufi’s winning project from the 2020 Open Call for Art Jameel Commissions: Digital, in 2020, and was released online in February 2021. It won Best Experimental Short Film at Sharjah Art Foundation’s Sharjah Film Platform, in November 2021.

I spoke to Nadim about the film and market driven futures.

Hind Mezaina (HM): Your film includes tropes found in corporate videos about futuristic places, and two voice overs that sound like they are reading letters to each other, or to the viewer. What was your thought process behind this film?

Nadim Choufi (NC): Rendered images usually try to present a perfect world, or to be more precise, a perfect object. If it is a representation of a perfect environment, how do you achieve it, what type of sociopolitical decisions are made to achieve it?

For the voice over script, I didn't want to find an alternative view of the future. If this is a future that's being imposed through existing renderings, then what type of script can I write to actually fully understand what it means to live in that world.

It was an experiment for me to imagine what life looks like in a perfect world, like The Truman Show. The script was written specifically for Dayna Ash and Jad Wadi, the two voices you hear—I had them in my mind to do the voiceovers. I wondered how the two protagonists in the film would feel in these spaces.

There's a part in the script where Jad talks about how there isn’t enough of a night time for him to walk someone home, or to pick someone up, for a certain emotion or desire. Dayna also tries to imagine her partner under different suns and different shadows, about body fatigue, and the upkeep of these rendered worlds that are often invisible.

The worlds in rendered images are usually devoid of any human interaction, so I added voices to infuse them with very intrinsic human emotions and desires, and to question if they actually have the capacity to hold any human desire or emotion in these spaces. Are they even made to be lived in, or just to present an empty solution?

HM: In Dubai, we’re surrounded by marketing campaigns about future projects, and it isn't a recent occurrence, but has been ongoing for decades. There’s a constant pursuit of building a future and a lack of assessing the present. Are there other cities that are similar?

NC: Maybe what's spectacular about Dubai is how it’s more like a corporation—there’s a bias that’s closer to a tech company than it is to a city, which for me is almost remarkable.

Beirut was like that during the reconstruction and real estate boom that happened more than ten years ago. The city was flooded with images of how the city would look, and it was often done on land that was destroyed in the war, that would be rebuilt in a very neoliberal way.

Other cities like Los Angeles, for example, market an individual dream, very different to how Dubai markets a collective future with the same approach as tech companies, because they use the same message: technical innovation will solve our problems.

You start questioning what the logic is behind all of this. Is it about dominating this field—a human desire to dominate this space rather than to save it? There’s a fine line between preserving and possessing something, whether it's nature, ecology, the environment, or the world.

HM: Sustainability has become even more important now, but it always feels like capitalism wins, and any positive efforts or good examples of sustainability belong in the margins of society. Although technology is being promoted as something that helps create equality and accessibility, I think it creates even more inequality. Even concepts like “smart cities” make me wonder how much more isolation it could create within society.

NC: For the technologies that are being used to connect us, we need to look at the desire of the user versus the desire of the designer.

The desire of the user is to connect with others, but the designer wants to keep your attention on their product and to make money. This is how smart cities operate; we’re told they make life easier, but actually they keep a certain idea of production and political progress intact.

So in the same way that many people realized how lonely they are, even through a collective pandemic—and by lonely, I mean both the emotion but also being alone—I think smart cities do the same thing.

That's why the film really focuses on how alone the protagonists feel; or how they long for something that they could or might have; or how much their lifestyle can incorporate their desires, regardless of the type, in the city without it being a lifestyle that's proposed by the city.

I was looking at the design of life cycle in smart cities, because for instance, the air you breathe is supposed to then be taken in by the plants. So there’s a need to know how many plants and how many people are needed. The concept of life in these smart cities is usually reduced to functionality and replaceability. If you're functional, how much are you producing? Can you be replaced?

So that was important in making the film, having homogenous plants inside the architecture, because they’re needed to feed the humans. It's not about preserving the completeness of environmental biodiversity. It's about keeping a certain cycle, and not the whole earth, alive.

In the scenes where a horse and a tiger drop into bowls, I was thinking about Noah's Ark, and Spaceship Earth, one of the first instances that people thought about a closed system. These so-called smart cities are like miniatures of Spaceship Earth or Noah's Ark, and if it is about saving life, how do you do it? What would a market-driven Noah's Ark look like?