The Lunatic as Anticolonial: Mona Benyamin’s Moonscape

Text by Jad Dashan

The Moon has long been muse to countless creatives, brimming with mystery, possibility, and romance. As a beacon of futurity and hope, it has inspired numerous Palestinian artists living under Israeli occupation and in the diaspora to make space for realities alternative to their homeland’s seventy-three-year colonization. Among them, filmmaker and visual artist Mona Benyamin turns to Luna in her short film, Moonscape (2020).

Spanning seventeen minutes, the film-noir-flavored piece follows the artist’s inquiries into Dennis M. Hope’s Lunar Embassy and probes questions of settler-colonialism, nostalgia, despair, and hope. Hope founded his Embassy in 1980, when he declared undisputed ownership of the moon and began selling extraterrestrial property. Moonscape launches from Benyamin’s dismal realization that, given just an internet connection, a Palestinian refugee is currently more likely to own land on the moon than return to their colonized homeland on Earth.

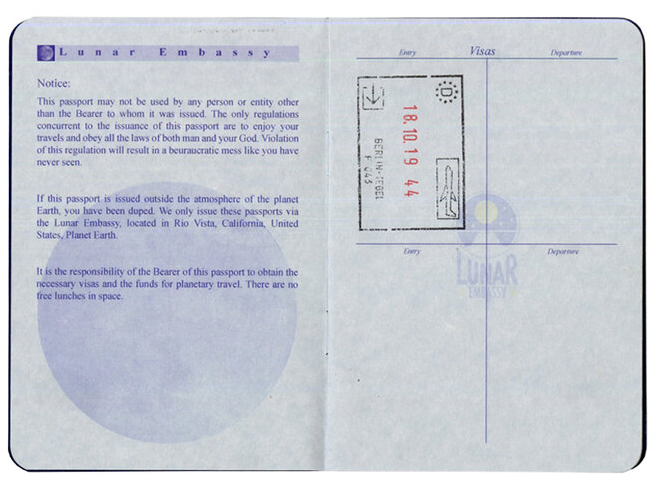

Eventually, Benyamin learns of the Galactic Passports that the Lunar Embassy sells and acquires one. It is her hope that this document will allow her to visit neighboring countries like Lebanon and Syria, which she cannot enter as a Palestinian born in Haifa and holding an Israeli passport. Yet, even as a lunar citizen, the plan fails and Benyamin is told to kiss her dreams goodbye.

Since the 1948 Nakba, or Catastrophe, when more than 700,000 indigenous Palestinians were expelled from their land and approximately 13,000 were massacred by Zionist forces, Israel has sustained itself through the genocide, mass incarceration, and human rights abuse of Palestinians. While further investigating the Lunar Embassy’s work, Moonscape evokes eerie parallels between the company’s colonialist dominion over the Moon and Israel’s colonization of Palestine. This includes how NASA’s prerogative to displace lunar inhabitants mirrors Israel’s ongoing ethnic cleansing of Palestinians. These common threads stretch back to the Lunar Embassy’s initial founding through a loophole in the 1967 Outer Space Treaty issued by the United Nations, whose inaction proves instrumental to the occupation of the Moon as well as Palestine.

The parallel trajectories of the Moon and Palestine are not coincidental, for the histories of space flight and colonialisms are tightly bound. The United States’ exuberant space missions in the 60s, which first placed “Whitey on the Moon” (as Gil Scott Heron famously observed) would not have been possible without the massive amounts of capital the country accumulated through centuries of colonial exploits and slavery. What is more, in spite of the aforementioned Outer Space Treaty (coincidentally the same year as the Palestinian Naksa), space is heavily militarized, stretching imperial project to the cosmos.

Benyamin’s film is formatted as a segment being broadcast on a fictional television channel, invoking satellite orbits and the ethereal signals of global communication systems suspended in space. The cartooned visuals of space in the channel’s logo and intermission emphasize the role of outer space as the medium conveying Benyamin's narrative and incubating the anticolonial dreams underlying Moonscape. Additionally, they highlight how the infinite void of space is tensely electrified with the glimmering promise of liberation as well as the histories and technologies of modern imperialism.

Mona Benyamin, film still, from Moonscape still (2020).

Moreover, by employing surrealist film techniques and referencing scenes from surrealist films, Moonscape underlines the relationship between the Moon, a symbol of the Unconscious, and the Surrealist movement, one preoccupied with its inner-workings. Like countless surrealist works, many images in Moonscape, like the house buoyed by balloons, estrange elements of the everyday. Other images allude to iconic, surrealist depictions of the Moon such as Georges Méliès’ Le Voyage dans la Lune (1902) and Luis Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou (1929).

Benyamin’s channeling of the surreal harnesses the movement’s anticolonial ethos: the idea that unlocking unconscious dreams, desires, and hopes could transform the dominant, colonial world order of “borders, soldiers, and walls.”

Within the reality of militarized space, for the colonized to claim space—in space—is not only surreal, but a radical and utopian gesture as it breaks away from the overbearing rationale of global imperialism. More than a decade ago, seminal Palestinian filmmaker Larissa Sansour took "a small step for a Palestinian, a great leap for humanity" in A Space Exodus (2008). The short film imagines the first Palestinian astronaut planting the Palestinian flag on the Moon, but ends with this “Palestinaut” floating away into the cosmos as she calls out for Jerusalem. This tragic denouement could be read as the futility of re-appropriating colonial power structures in the struggle to decolonize. In some ways, Benyamin’s Moonscape tackles that same failure. Yet, Moonscape is not science-fictional or futurist in that sense. Rather than prescribing a utopia, Moonscape zeroes in on the onerous futility of the Lunar Embassy’s colonial bureaucracies (and by implication those which Palestinians face daily), thus opening avenues to begin imagining different futures.

Using surrealist techniques, humor, and tropes of popular Arabic music, Moonscape contends with the failure of co-opting colonial mechanisms, whether space colonization or claims of celestial citizenship, in order to restore what the colonizer has stolen. Benyamin’s work offers up a lunatic way of thinking: one that is decidedly out of this world; one which can only be registered as illogical and unthinkable through colonial, white supremacist frames of thought; and one which is nostalgic, hopeful, and humorous.